Sleep requirements in children: An evidence-based guide

© 2008-2014 Gwen Dewar, all rights reserved

What are your child's sleep requirements? Even the experts don't know for sure.

Slumber has a big impact on our well-being, and so information technology's understandable that parents want to know if their kids are getting enough. opens in a new windowRecent research suggests that something every bit simple as a well-timed nap makes a departure in how much preschoolers learn (Kurdziel et al 2013). Naps may likewise opens in a new windowenhance learning in babies.

But while information technology's clear that sleep is of import, in that location is no easy formula for calculating your child's personal sleep needs. In fact, the almost surprising thing about sleep requirements is how little we know about them (Hunt 2003).

The official-looking recommendations we see everywhere, like the ones in the box below from National Sleep Foundation, are often based on studies of how much time people spendin bed.The charts don't tell u.s. how much of this fourth dimension is actually spent sleeping.

Nor do they tell u.s.a. about how sleep varies cross-culturally. Typically, recommendations about sleep requirements are based on surveys of Western populations (eastward.1000., Blair et al 2012; Iglowstein et al 2003; Armstrong et al 1994; Roffwarg et al 1966).

Most importantly, the charts tin can't tell us what your individualized needs are.

Knowing how much time people spend in bed is somewhat helpful, but it doesn't tell us if these people are getting the right amount of slumber.

As the National Center on Sleep Disorders Enquiry has noted, we need large-calibration, controlled studies that measure both sleep and biological outcomes (Hunt 2003). Unfortunately, such studies are uncommon.

Notable exceptions are studies focusing on beliefs bug and obesity.

For example, a study of 297 Finnish families with children aged 5-6 years, researchers found that kids who slept less than ix hours each day had 3-5 times the odds of developing attention problems, behavior bug, and other psychiatric symptoms (Paavonen et al 2009).

Another recent report tracked the development of obesity in young children.

In that report, researchers recorded the body weights and sleep habits of kids nether five years of age. And then, five years later, they measured the kids again.

The study revealed a link betwixt sleep loss and obesity. Kids who'd gotten less than ten hours of night sleep at the beginning of the study were twice equally probable to go overweight or obese after on (Bong and Zimmerman 2010).

Moreover, researchers establish that the timing of sleep mattered. When information technology came to reducing the risk of obesity, daytime naps didn't aid. For young children, the crucial factor was getting more than x hours of slumber at dark.

Is the evidence conclusive? No. Some enquiry has failed to find links between sleep time and fat accumulation, like ane study of children nether the historic period of 3 (Klingenberg et al 2013), and of course we tin can't exist sure about causation.

Some kids may suffer from medical weather that cause both sleep problems and obesity. Perhaps in the most future investigators will resolve these discrepancies.

Meanwhile, how practice nosotros know what's normal?

Nosotros tin can endeavour to answer these questions past consulting the range of sleep times that are typical for many infants, children, and adults (see the tables below).

But keep the following points in mind:

ane. At that place is no optimal number of sleep hours that applies to all adults or all kids (Bewilder and Vaughan 1999; Jenni et al 2007).

Slumber requirements are probably influenced by growth rates, stress, affliction, pregnancy, and other aspects of your physical status. They may also be influenced past your genes (Gottlieb et al 2007).

ii. The most recent scientific report of sleep duration amid children reveals a tremendous amount of variation betwixt individuals–peculiarly during early babyhood.

For example, newborns may slumber anywhere from nine to 19 hours a solar day (Iglowstein et al 2003). Kids at both ends of the spectrum may exist healthy and normal.

3. Sleep patterns vary cantankerous-culturally.

In some cases, cultural differences are mostly most the scheduling of sleep.

For instance, in predominantly Asian countries, preschool children get less sleep at dark than practise kids in predominantly Caucasian countries, but they make up the shortfall by napping during the day (Mindell et al 2013).

In other cases, cultural differences concern the total amount of slumber people get over a 24-hour period.

Kids in China and Italia appear to get less sleep than exercise children in the Netherlands and the United States (Ottaviano et al 1996; Lui et a 2003; Super et al 1996). Who is ameliorate off? At present, we lack scientific studies that address this question (Jenni and O'Connor 2005).

Meanwhile, we shouldn't assume that the "boilerplate sleeper" in any given study is getting the optimal amount of sleep. Some populations may be chronically under-slept; others may exist well-rested.

4. In Western countries, recommended sleep durations have changed over fourth dimension.

For example, in the early 1900s, several sleep experts were advising that toddlers (age one-2 years) get 17-18 hours of sleep (Matricciani et al 2013).

Today, the National Sleep Foundation says that it'due south normal for children in this age group to get 11-fourteen hours.

Accept toddler sleep requirements changed since the 20th century? It seems very unlikely. Official, population-broad recommendations reflect guesswork and cultural norms; they shouldn't override our personal observations of a child's energy levels, moods, or signs of fatigue.

v. Also little sleep can have of import wellness consequences.

Scientific studies link childhood sleep loss with fatigue and bad moods (Oginska and Pokorski 2006; Berger et al 2012), attention problems (Fallone et al 2001), impaired retentiveness consolidation (Kurdziel et al 2012), bookish problems (Fallone et al 2005), and obesity (Lumeng et al 2007; Bong and Zimmerman 2010).

6. Merely s leeping less than average isn't necessarily bad.

Some kids sleep less than others, and they don't always suffer for it. For example, researchers tracking the sleep habits of Swiss children found that individual differences in sleep fourth dimension were not correlated with differences in growth. (Jenni et al 2007).

7. Although some parents underestimate how much sleep their children need, others overestimate.

Earlier imposing any particular slumber schedule on your child, it'southward important to determine what your child's own, individual sleep requirements are. Forcing children to become to bed when they aren't sleepy can cause opens in a new windowbedtime battles and other behavior problems.

What'southward typical in the 21st century, English-speaking world?

Clues from a study of British children

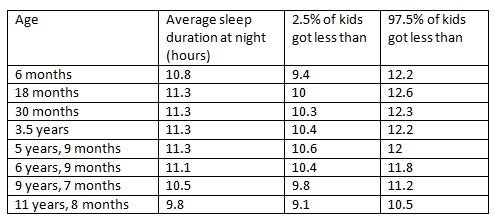

The tabular array beneath reports the results of a big, prospective study of more than xi,500 kids built-in in South-West England in 1991-1992.

At 8 different points in time – kickoff when the children were 6 months old and ending when they were eleven years old — Peter Blair and his colleagues (2012) asked parents when their kids "usually went to bed in the evening and woke in the morning time on an average weekday."

From these data, the researchers calculated how much time kids spent in bed each nighttime. Because parents rarely know precisely when their children autumn asleep or wake up—or how much time kids spend awake in the middle of the night—these parental reports probably overestimate the amount of time kids actually slept (Jenni et al 2007).

The tabular array shows the average dark sleep duration for each age group (Blair et al 2012).

It besides provides data about the degree of variation. For example, the table indicates that 95% of preschoolers (aged approximately 3.5 years) slept between x.4 and 12.2 hours. Simply 2.5% got less than 10.3 hours, and only 2.5% got more than 12.iii hours.

Note: For more detailed data about infant slumber times, see this article on opens in a new windowbabe sleep requirements.

What about naps?

The researchers besides asked about daytime slumber. Amongst children who napped, how much time did they log in bed? Here are the results:

- 6 months: two.iv hours average; range i.three – 3.5 hours

- 18 months: 1.5 hours average; range one – 2 hours

- xxx months: 1.ii hours average; range 0.7 – one.7 hours

- 3.five years: 1.1 hours average; range 0.5 – 1.7 hours

- 5.75 years: 1 hours average; range 0.3 – 1.vii hours

- 6.75 years: ane.2 hours average; range 0.3 – 2.ane hours

Most all children 18 months and younger were reported to have naps. Most children (59%) still took naps at the historic period of 30 months. Just by the time kids were 3.5 years of historic period, only 23% slept during the day, and reports of napping were very uncommon for kids older than five years.

The British data are probably consistent with practices in other Northern European and Anglo cultures—-cultures where daytime slumber is discouraged for older children and adults (east.yard., Republic of iceland: Thorleifsdottir et al 2002, Switzerland: Iglowstein et al 2003).

Merely the truth is that human beings are very flexible about when and how they run into their sleep requirements.

In many parts of the earth, napping is a normal part of life for children and adults (Worthman and Melby 2002).

In fact, as I noted in my article well-nigh opens in a new windowdark wakings, the historical and anthropological evidence suggests that humans were designed to slumber flexibly (Worthman and Melby 2003; Ekirch 2005).

Then the British study is not representative of kids living in "pro-napping" or "siesta" cultures.

For instance, in Saudi Arabia, napping is common among older kids. According to a written report of school-age children in Riyadh, 45% of thirteen-year olds take regular naps (BaHamman et al 2006).

And even in countries where napping is discouraged past the mainstream, specific ethnic groups may encourage napping. In the Southern U.s.a., African-American kids are much more likely to nap—and to nap more frequently—than are European American kids (Crosby et al 2005). In 1 study, 40% of African-Americans were nonetheless taking naps at eight years of age (Crosby et al 2005).

Is the early abandonment of napping detrimental? For some kids information technology might be. Recent experimental research indicates that toddlers who skip naps are more than likely to (1) prove defoliation and negative emotion in response to challenging tasks (Berger et al 2012) and (ii) take problem "downloading" new data into long-term retention (Kurdziel et al 2013).

Are kids today meeting their slumber requirements?

The British study tells u.s.a. about what'due south normal amidst a certain population of children. But what's normal keeps changing. Equally the authors annotation, their results differ substantially from the results of older, earlier studies of Western children.

For instance, a major written report of Swiss kids born in the 1970s reported that babies and toddlers got almost an hour more slumber each night than did the more contemporary, British children (Iglowstein et al 2003).

The mod British kids are likewise falling short of the National Sleep Foundation'southward recommendations about sleep requirements (every bit noted above). And that's in keeping with an international trend towards shorter slumber times for kids.

From the The states to Saudi Arabia to Hong Kong, recent studies indicate that kids are sleeping less than experts typically recommend (Matricciani et al 2012; BaHammam et al 2006; Ng 2005 Smedje 2007; Tynjala et al 1993).

Is this worrying?

As I note higher up, information technology's difficult to say how much sleep the average kid needs for optimal wellness. We need more rigorous, focused research to answer that question.

But given evidence to date that links shorter slumber duration with obesity (mentioned to a higher place), attention problems, emotional problems, and dumb academic functioning (Vriend et al 2013; Li et al 2013), I call back we should exist concerned. Some kids may discover their personal needs are in-sync with the modern trend towards shorter sleep times. But others may not.

Fine-tuning: Your family's individualized sleep requirements

Sleep charts may give usa a rough thought of what is considered normal. But the best guide to your ain sleep requirements is how y'all feel and perform (Dement and Vaughan 1999). There are several ways to take stock of your individualized sleep requirements-—and the individualized sleep requirements of your kids.

Co-ordinate to Stanford researcher and world-renowned sleep expert William C. Dement, the best manner to determine your own slumber requirements is to go along a sleep diary. This involves noting the fourth dimension you go to bed, the approximate fourth dimension it takes for you to autumn comatose, and the time you awaken in the morning. It also involves keeping track of how sleepy you experience during the solar day (Bewilder and Vaughan 1999).

You lot tin prefer this arroyo for your kids, too. In general, you lot are probably not getting plenty sleep if

- you are sleepy at the wrong fourth dimension of twenty-four hour period (due east.g., after waking in the morning);

- yous take trouble paying attending during the day,

- yous tend to autumn asleep very chop-chop (within a few minutes) when given the chance; or, paradoxically,

- yous are "wired" at the wrong time of day (eastward.one thousand., only before bedtime).

These principles apply to kids, too. Studies reveal other symptoms of slumber deprivation in kids (Dahl 1996), including:

- a child who is easily frustrated and quickly irritated

- a kid who has problem keeping his impulses in bank check

For more help determining your family unit'southward individualized sleep requirements, opens in a new windowclick hither. You'll find more details almost Bewilder'southward approach, equally well as a guide to signs of sleep deprivation in babies and young children.

When yous fail to meet your sleep requirements: The health consequences

Nosotros may demand more rigorous studies about the optimal duration of slumber. But there is no lack of evidence regarding the consequences of severe sleep brake. In controlled, experimental studies, volunteers assigned to alive on very little slumber (typically, 4 hours or less) suffered from the following problems:

- impaired considerateness (Fallone et al 2001);

- impaired power to retain new memories (Yoo et al 2007a);

- impaired immune system (Rogers et al 2001);

- greater emotionality (e.one thousand., condign more upset by disturbing images—Yoo et al 2007b);

- increased afternoon and evening cortisol (stress hormone) levels (Copinschi 2005); and

- increased feelings of hunger (which may atomic number 82 to overeating—Copinschi 2005).

Other, correlational research hints at long-term problems for people who deviate from the the modernistic norm.

For example, a study of American adults (ranging from thirty-102 years old) showed that people who habitually slept about vii hours a night had the best survival rates. People who reported either

(1) sleeping less than half-dozen hours a night, or

(2) sleeping more 8 hours a night

were more likely to die (Kripke et al 2002).

Interestingly, a dissever study of Japanese adults (between xl-79 years of age) had similar results: Sleeping more or less than vii hours was associated with higher mortality (Tamakoshi and Ohno 2004).

This research got a lot of media attending when it was published, and many headlines unsaid that there was a causal link between sleep duration and mortality.

But we can't yet draw any conclusions about causation. As the study authors noted, their research design can't tell u.s. why people who get more than or less slumber are at higher risk. Habitually "short" and "long" sleepers may suffer underlying health problems that cause both sleep disturbances AND increased mortality.

For case, people with sleep apnea are less efficient sleepers, and may have to sleep longer hours in society to achieve minimal levels of alertness during the day. Only sleep apnea patients are too more likely to suffer dangerous wellness problems, and they are at greater risk of dying while they sleep.

Other life-threatening medical conditions may crusade people to sleep longer or shorter than average, resulting in a correlation between long sleep duration and mortality.

The bottom line?

Sleeping more or less than average may be a symptom of an underlying health problem that causes increased bloodshed. But it may also reflect your perfectly good for you, individually-determined sleep needs. If you habitually sleep much less or much more than average, you lot might want to take your doc check you lot for such health issues as eye disease, sleep apnea, and depression.

References: What scientific studies suggest about human sleep requirements

Armstrong KL, Quinn RA, and Dadds MR. 1994. The sleep patterns of normal children. Med Journal of Commonwealth of australia 161: 202-206.

Ashworth A, Colina CM, Karmiloff-Smith A, and Dimitriou D. 2013. Slumber enhances memory consolidation in children. J Sleep Res. 2022 Dec 16. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12119. [Epub ahead of print]

BaHammam A, Bin Saheed A, Al-Faris E, and Shaihk Due south. 2006. Sleep duration and its correlates in a sample of Saudi schoolhouse children. Singapore Medical Journal 47: 875-81.

Barbato M, Barker C, Bender C, et al.1994. Extended sleep in humans in fourteen hour nights (LD 10:xiv): relationship between REM density and spontaneous awakening. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. xc:291-297.

Bell JF and Zimmerman FJ. 2010. Shortened Nighttime Sleep Duration in Early Life and Subsequent Childhood Obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 164(9):840-845.

Berger RH, Miller AL, Seifer R, Cares SR, LeBourgeois MK. 2012. Acute sleep restriction effects on emotion responses in 30- to 36-month-sometime children. J Sleep Res. 21(three):235-46.

Blair PS, Humphreys JS, Gringras P, Taheri South, Scott N, Emond A, Henderson J, and Fleming PJ. 2012. Childhood sleep duration and associated demographic characteristics in an English language cohort. Sleep ;35(three):353-60.

Copinschi G. 2005. Metabolic and endocrine effects of sleep impecuniousness. Essent Psychopharmacol. six(6): 341-347.

Crosby B, LeBourgeois MK, and Harsh J. 2005. Racial differences in reported napping and nocturnal slumber in two to 8-yr-former children. Pediatrics 115: 225-232.

Dahl RE 1996. The impact of inadequate sleep on children's daytime cerebral office. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology 3: 44-50

Dement Westward and Vaughan C. 1999. The promise of sleep. New York: Random Firm.

Ekirch AR. 2005. At 24-hour interval'south Close: Night in Times By. New York: WW Norton.

Fallone K, Acebo C, Arnedt JT, Seifer R, and Carskadon MA. 2001. Effects of acute slumber restriction on beliefs, sustained attending, and response inhibition in children. Percept Mot Skills 93: 213-229.

Fallone Chiliad, Acebo C, Seifer R, Carskadon MA. 2005. Experimental restriction of sleep opportunity in children: Effects on teacher ratings. Sleep 28(12): 1561-1567.

Gais Southward, Lucas B and Born J. 2006. Sleep subsequently learning aids retentivity remember. Learning and Memory thirteen: 259-262.

Galland BC, Taylor BJ, Elderberry DE, Herbison P. 2012. Normal slumber patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Med Rev. xvi(iii):213-22.

Gottlieb DJ, O'Connor GT, and Wilk JB. 2007. Genome-broad association of sleep and circadian phenotypes. BMC Medical Genetics 8(Supplement 1): S9-S16.

Gruber R, Laviolette R, Deluca P, Monson E, Cornish K, and Carrier J. 2010. Brusk sleep duration is associated with poor performance on IQ measures in healthy school-historic period children. Sleep Med. 11(three):289-94.

Chase CE. 2003. National sleep disorders inquiry programme. Bethesda, MD: National Center on Sleep Disorders Research.

Iglowstein I, Jenni OG, Molinari 50, Largo RH. 2003. Sleep duration from infancy to adolescence: Reference values and generational trends. Pediatrics 111(2): 302-307.

Jenni OG, Molinari L, Caflish JA, and Largo RH. 2007. Sleep Duration From Ages 1 to 10 Years: Variability and Stability in Comparison With Growth. Pediatrics 120(4): e769-e776.

Jenni OG and O'Connor BB. 2005. Children's slumber: An interplay between culture and biological science. Pediatrics 115: 204-215.

Jenni OG, Zinggeler F, Iglowstein I, Molinari L, and Largo RH. 2005. Pediatrics 115(ane): 233-240.

Klingenberg L, Christensen LB, Hjorth MF, Zangenberg S, Chaput JP, Sjödin A, Mølgaard C, and Michaelsen KF. 2013. No relation between sleep duration and adiposity indicators in ix-36 months quondam children: the SKOT cohort. Pediatr Obes. viii(1):e14-8.

Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR 2002. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Curvation Gen Psychiatry 59:131-136.

Kurdziel L, Duclos K, and Spencer R. 2013. Sleep spindles in midday naps enhance learning in preschool children. PNAS (epub ahead of print) doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306418110.

Kurdziel L, Duclos K, and Spencer R. 2013. Slumber spindles in midday naps heighten learning in preschool children. PNAS (epub alee of print) doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306418110.

Largo RH and Hunziker UA. 1984. A developmental approach to the direction of children with sleep disturbances in the first 3 years of life. Euro Journal of Pediatrics 142: 170-173.

Lavigne JV, Arend R, Rosenbaum D et al. 1999. Slumber and behavior issues among preschoolers. Journal of Dev Behav Pediatr. 20: 164-169.

Leproult R, Copinschi G, Buxton O, and Van Cauter E. 2007. Sleep loss results in an meridian of cortisol levels the next evening. Slumber 20(x): 865-870.

Li S, Arguelles L, Jiang F, Chen W, Jin 10, Yan C, Tian Y, Hong X, Qian C, Zhang J, Wang X, Shen X. 2013. Sleep, school performance, and a school-based intervention amid schoolhouse-aged children: a sleep series report in China. PLoS One. eight(seven):e67928.

Lui Ten, Lui L, and Wang R. 2003. Bed sharing, sleep habits, and sleep issues amongst Chinese school-aged children. Sleep 26: 839-844.

Lumeng JC, Somashekar D, Appulgliese D, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, and Bradley RH. 2007. Shorter sleep elapsing is associated with increased risk for being overweight at ages 9 to 12 years. Pediatrics 120: 1020-1020.

Matricciani LA, Olds TS, Blunden Due south, Rigney One thousand, Williams MT. Never enough sleep: a brief history of sleep recommendations for children. Pediatrics. 129(3):548-56.

Maquet P. 2001. The role of sleep in learning and retentivity. Scientific discipline 294: 1048-1052.

Mednick S, Nakayama K, and Stickgold R. 2003. Sleep-dependent learning: a nap is equally good as a night. Nature Neuroscience 6: 697-698.

Mindell JA, Sadeh A, Kwon R, Goh DY. 2013. Cross-cultural differences in the sleep of preschool children. Slumber Med. xiv(12):1283-9.

Ng DK, Kwok KL, Cheung JM, et al. 2005. Prevalence of sleep issues in Hong Kong primary school children: a community-based telephone survey. Chest 128: 1315-1323.

Oginska H and Pokorski J. 2006. Fatigue and mood correlates of sleep length in iii age-social groups: Schoolhouse children, students, and employees. Chronobiol. Int. 23: 1317-1328.

Ottaviano S, Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Bruni O, Ottaviano C. 1996. Slumber characteristics in good for you children from birth to 6 years of historic period in the urban area of Rome. Sleep xix: 1-iii.

Paavonen EJ, Porkka-Heiskanen T, and Lahikainen AR. 2009. Sleep quality, duration and behavioral symptoms among 5-6-year-old children.Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Dec;eighteen(12):747-54.

Rogers NL, Szuba MP, Staab JP, Evans DL, and Dinges DF. 2001. Neuroimmunologic aspects of slumber and sleep loss. Semin. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 6(4): 295-307.

Roffwarg HP, Muzic JN, and Bewilder WC. 1966. Ontogenetic development of the human slumber-dream bike. Science 152: 604-619.

Shur-Fen Gau Southward. 2006. Prevalence of sleep issues and their association with inattention / hyperactivity among children anile 6-15 in Taiwan. Journal of Sleep Research 5(4): 403-414.

Smedje H. 2007. Australian study of 10- to 15-year olds shows pregnant decline in sleep duration between 1985 and 2004. Acta Paediatrica 96 (7): 954–955.

Super CM, Harkness S, and van Tijen Northward. 1996. The iii R'south of Dutch childrearing and the socialization of infant arousal. In S. Harkness & C.M. Super (Eds.), Parents' cultural belief systems: Their origins, expressions, and consequences (pp. 447–466). New York: Guilford Press.

Super CM and Harkness S. 1982. The baby's niche in rural Republic of kenya and metropolitan America. In: Cantankerous-cultural Research at Issue, pp. 47-55, L.L. Adler (Ed.). New York: Academic Printing.

Tamakoshi A and Ohno Y. 2004. Self-reported slumber duration as a predictor of all-cause bloodshed: results from the JACC study, Japan. Sleep 27(1):51-iv.

Thorleifsdottir , Bjornsson JK, Benediktsdottir B, Gislason T, and Kristbjarnarson H. 2002. Sleep and sleep habits from babyhood to immature adulthood over a 10- year period. Journal Psychosom Res 53: 529-537.

Toth LA. 2001. Identifying genetic influences on slumber: AN approach to discovering the mechanisms of sleep regulation. Behavior genetics 31: 39-46.

Tynjala J, Kannas L, and Valimaa R. 1993. How young Europeans slumber. Health Educ Res 8: 69-80.

Vriend JL, Davidson FD, Corkum PV, Rusak B, Chambers CT, McLaughlin EN. 2013. Manipulating sleep elapsing alters emotional functioning and cerebral operation in children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2022 Nov;38(10):1058-69.

Worthman CM and Melby Yard. 2002. Toward a comparative developmental ecology of human slumber. In: Boyish Sleep Patterns: Biological, Social, and Psychological Influences, M.A. Carskadon, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 69-117.

Yoo SS, Gujar N, Hu, Jolesz FA, and Walker MP. 2007a. The human emotional brain without sleep—a prefrontal amygdale disconnect. Current Biology 17(20): 877-878.

Yoo SS, Hu PT, Gujar North, Jolesz FA and Walker MP. 2007b. A deficit in the ability to form new human being memories without slumber. Nat Neurosci 10(3): 385-392.

Content of "Slumber requirements" last modified 1/14

Photograph credits for sleep requirements article:

image of yawning boy ©iStockphoto.com/Bronwyn8

epitome of eagle owl ©iStockphoto.com/Dirk Freder

Source: https://parentingscience.com/sleep-requirements-2/

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Sleep requirements in children: An evidence-based guide"

Posting Komentar